February 25, 2013

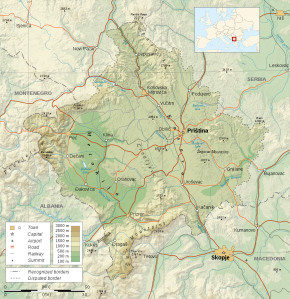

I have thought daily of my students in Kosova over the eight months since my return to the USA. Thanks to emails from Besa, Gezim, Arlind, and Ragip, the seven time zones that separate us seem a bit less immense. They all report missing me as much as I miss them, a sentiment that means more to me than they may realize; they report, too, that the research writing they did in our Twentieth-Century American Literature class has served them well in subsequent courses, particularly on their major paper on Toni Morrison.

(L to R) Armind, Arlind, Fidan, me, Bajram, Laurita, Dafina, Shkodran, Ragip, Albana, Gezim, June 2012

behind Judy and me, (L to R) Besa, Fidan, Blerta, Kadrie, Edita, Merita, and Xhemile, June 2012

In my next email to these four students and to their 18 colleagues, I will urge them to return to this blog, where they can reminisce with me about our six months together and, just as important, where they will discover how much they continue to influence by writing. As it turns out, this blog has served as a rough draft for a book I have written. Titled Writing Visions of Hope: Teaching Twentieth-Century American Literature and Research, the book narrates our collaborative reading and writing in these two courses. More than an account of writing-to-learn pedagogy, the book narrates my students’ stories and ties their lives to modern and contemporary literature of the Balkans as well as to the literature of America, 1901-2000. This book will appear, I’m guessing, in May or June of 2013, one year after my departure; it will be published by Information Age Publishing. I will certainly alert all my blog friends as well as my students when the book enters the world.

Additionally, the journal Pedagogy, published by Duke University Press, will soon publish an article on my work with these Kosovaran students, focusing primarily on our study of poetry. This piece, titled “Considering Claims and Finding One’s Place,” should also reach print sometime in 2013.

I also hope that my Kosovaran students will return to this blog to see how they continue to influence my teaching here at Mississippi State University. In the fall of 2012, for instance, I taught a writing course for first year students. Remembering how much my students at the University of Pristina enjoyed journaling on poetry, not only to learn how to analyze the poems but also to find personal connections to the poet’s stories, I used the same approach with these young American students, who read, among other poems, Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish,” one of the poems my UP students read. Using the very same journaling prompts I assigned in Kosova, I asked my students to study the “five-haired beard of wisdom” and other figures and details that taught us to see the beauty of this grotesque fish and to hear the speaker’s joy as she decides to “let the fish go.”

But, remembering the energy of my Kosovaran students, prompted by our readings, as they narrated their lives, I asked these American students to consider writing an essay, grounded in their journaling on Bishop’s “The Fish,” that narrates one of their own experiences in the world of nature, one that changed the way they think about nature and their own place in the natural world. Many students took this option, one which produced some of the best writing of the semester. Attached, you’ll find a sample of this nature writing, Trip Kennon’s essay on “The Face of the Ozarks.”

John Bickle, Professor and Head, Philosophy & Religion (Source: Univ. of Cincinnati)

This winter/spring semester, with philosopher Dr. John Bickle, I’m team-teaching a Humanities course for third-year undergraduates, a course that blends studies in philosophy—Dr. Bickle’s department—with readings in Western American novels focused on the Frontier experience—my department. Our students also relate their readings in philosophy and literature to classic movies on the American West: “Shane,” the 1953 film on the clashing destinies of cattle men, “sod-busters,” and loners like Shane; “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” the 1962 cinema that examines frontier justice, juxtaposing the rule of the gun with the rule of law; “Hombre” (1967) and “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975), films that explore the tension between selfishness and self-sacrifice that informs the heroic code.

- Shane (1953) (Source: IMDb.com)

- The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) (Source: IMDb.com)

- Hombre (1967) (Source: IMDb.com)

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) (Source: IMDb.com)

A.B. Guthrie, Jr. and his daughter Gus Miller (Source: Main Hall to Main Street, University of Montana)

Drawing again on my experience with students at the University of Pristina, I asked my American students to keep a journal as they read our first novel, A. B. Guthrie, Jr.’s The Big Sky (1947), the story of mountain man Boone Caudill, the ‘white Indian’ who ironically clears the way for westward expansion even as he flees from mid-nineteenth century American civilization east of St. Louis. For their first essay, we asked the students to “identify three characteristics that best define Boone Caudill’s character to clarify why novelist Wallace Stegner calls Boone a “doomed” hero of the frontier. What qualities strike you as heroic? What qualities undercut that heroism? How and why is Caudill doomed? Does his doom result from his heroic virtues, from his flaws, or from both? Does his doom result in part from forces exterior to his character?”

Cover of A.B. Guthrie’s The Big Sky (Source: amazon.com)

To help students to gather material for this essay, we asked them, just as I asked students in Kosova, to journal in response to analytical questions like these below, focused on Part Four of the novel, where Boone seems so happy with his Piegan wife Teal Eye, but then gets caught up in trail-blazing to Oregon and in jealousies that lead to his shooting of his dear friend Jim, the man whose life he had earlier saved from the frozen mountains:

- Boone has reached the age of 29, Teal Eye 22. How would you describe the sources of Boone’s happiness in this relationship and in his life as a Piegan?

- What evidence do we see here that the end draws near for Indians and for mountain men?

- How, why does Boone get drawn into Peabody’s Oregon project?

- Boone’s fatal choice to trail-blaze for Peabody leads to even stronger evidence of nature’s brutality and indifference to men and their “manifest destinies.” Find at least three passages that use description to develop this naturalistic theme.

- What qualities in Boone stand out here as he and Jim face death by freezing and death by starvation?

- Look up “pantheism” in the dictionary. Do you see any pantheism emerging here? Who seems to think most deeply about the spiritually of nature?

- We see Boone’s love for Jim even after it appears that Jim has betrayed him. What sequence of bad news and mistakes leads to Boone’s suspicion of Jim? How do the causes and effects of Boone’s rage help you to understand Stegner’s notion of Boone as a “doomed” hero?

As of this writing, the students haven’t written this essay yet, but their brilliant responses to these journaling prompts, which they shared in class—just like we did in Kosova—bode well for some wonderful essays.

In addition to these undergraduate courses, I have taught two MA-level courses: in fall 2012, Writing Center Tutor Training, in spring 2013, Composition Pedagogy. Writing Center pedagogy, of course, focuses on one-on-one teaching; I went into this course with great enthusiasm, having seen conferencing work so well at UP as my students moved through three drafts of their research papers on Death of a Salesman, A Lesson Before Dying, or some other work of their choice.

I approached the Composition Pedagogy course with equal enthusiasm, remembering that many of my students in Kosova aspire to become teachers. I recalled, too, that all of my UP students responded generously to my request to interview them concerning their literacy histories, particularly as those histories relate to their memories of the 1990s wars in the Balkans and to their aspirations as students and professionals. After my American MA students had read and journaled on several articles focused on how we learn to read and write and on how we might best help students in our classrooms to develop these literacies, I asked them to write a narrative essay, focusing on their own literacy histories, on their own writing processes, or on their observations of a master writing teacher (see assignment pdf), a request preceded, of course, by rough drafting and peer response sessions—precisely the strategies that worked so well in Kosova. If you will click on the attached files, you will find the excellent responses of Kiley, Aaron, Kayleigh, Jessica and Sharon; you will also see them depicted below.

(L to R) Kayleigh Swisher, Aaron Grimes, Sharon Simmons, February 2013

(L to R) Jessica Moseley, Kylie Forsythe, February 2013

Over the last two weeks, fellow Fulbrighter Dave McTier and I have enjoyed traveling in the Balkans, a region as rich in scenery as in history.

Over the last two weeks, fellow Fulbrighter Dave McTier and I have enjoyed traveling in the Balkans, a region as rich in scenery as in history.

Then on June 19, we took a bus to

Then on June 19, we took a bus to

The outskirts of Sophia reveal the same signs of poverty and displacement, but, as you will see in the photos, the inner city features grand government buildings, archeological museums, and innumerable mosques and Orthodox churches. As do other houses of worship in Europe, these offer rich iconography celebrating the faith-narratives of the past, but these shrines attract active believers, not just tourists.

The outskirts of Sophia reveal the same signs of poverty and displacement, but, as you will see in the photos, the inner city features grand government buildings, archeological museums, and innumerable mosques and Orthodox churches. As do other houses of worship in Europe, these offer rich iconography celebrating the faith-narratives of the past, but these shrines attract active believers, not just tourists.