May 14, 2012

As we gathered for the next session, I referred students to the board, where they saw a list of works from the postmodern period—post-World War II—that we had already read and discussed:

- Lahiri’s “Sexy” 1999

- Miller’s Death of a Salesman 1949

- Gaines’s A Lesson before Dying 1993

- Plath’s “Daddy” 1965

- Dove’s “Adolescence” 1980

- Lee’s “The Gift” 1986

- Gluck’s “Appearances” 1990

- Komunyakaa’s “My Father’s Love Letters” 1992

- Faulkner’s Nobel Prize Address, 1950

- King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” 1963

- Momaday’s The Way to Rainy Mountain 1969

In reviewing the list, I suggested that we could begin thinking about postmodernism as a continuation of modernism, particularly the interrelated themes of remembering as a basis for moving on, for making decisions about how to use our time, themes addressed in all the works listed here and in many of the works we would take up in these last four weeks. But the horror of World War II, especially its atomic ending, had such a traumatic effect on the entire culture, I said—as we saw in Faulkner’s question, “When will I be blown up”—that literary voices began to explore with new urgency the flux of our existence and its apparent absurdity. “Some of these voices,” I continued, “sound post modern in their rejection of T.S. Eliot’s allusive, academic ‘high modernism,’ as we will hear today in ‘The Fish’; others, as we will see in Vonnegut, sound postmodern in their unflinching explorations of the violent absurdities of our culture.”

I also spoke of postmodern “chaos theory,” the idea that human beings can collaborate in creating order, however tentative, from the randomness of experience, as we saw in Lahiri’s “Sexy.” “Miranda and Dev,” I reminded the students, “met by accident; then Miranda babysat for Rohin, an encounter she never planned; but she and Rohin collaborated in shaping a tentative order from the chaos the father’s adultery had caused, an order that disallows ‘loving strangers’ when such relationships root in deceit and crush the deceived.” By the end of that story, I concluded, Miranda had learned to open her eyes, “and her new wakefulness gave her the courage to end the affair.” This insistence on open eyes, I told the students, would inform every postmodern work we would read, and I challenged them to reflect on this idea of wakefulness as it might relate to Faulkner’s call for literature that gives us “hope,” that persuades us we can ‘endure and prevail.’

Bishop and Jarrell

Elizabeth Bishop (Source: Poetry Foundation)

Before we turned to Elizabeth Bishop’s 1946 poem “The Fish,” I asked the class to turn to her letter to her friend and fellow poet, Robert Lowell, whom she takes to task for writing poems about his recently divorced wife, poems that explore suffering but combine fiction and fact. In doing so, she tells Lowell, he has violated a trust with his former wife and with his readers, who can’t know “what’s true, what isn’t” (2498). “Postmodernists may consider “truth” a fluid, ever-changing phenomenon, but what does her remark to Lowell tell you about her sense of duty as a poet?” I asked. Earning a “10” for the day, Besa said the she shares Martin Luther King’s commitment to seeing accurately and publishing what one sees.

I thanked Besa for providing us a perfect transition to “The Fish” and asked Arlind to read the poem aloud. After Arlind’s reading, I re-read the first and last lines aloud: “I caught a tremendous fish….and I let the fish go.” I then asked for a show of hands, fisher-hands. Singling out Gezim among the fishermen and fisherwomen, I asked if he ever lets fish go. “Only if it’s too small,” he answered. “So why would she release a “tremendous” fish? Does her description, her use of figurative language in between the first and last lines, help us to understand her bizarre decision?” I asked. With no quick response forthcoming, I asked the class to focus on the first two lines, on facts and details about the fish. “What first strikes you as odd, given his size?” I asked. Ragip read line six: “He hadn’t fought at all.” He then mentioned that the “homely” fish looks warn-out, “battered.” “What about ‘venerable’? What does this word suggest?” Gezim offered that the fish must be venerated, respected, because he has fought many battles, “and his ‘skin hung in strips’” (ll. 8-10). “Don’t we normally use words like ‘homely’ and ‘venerable’ and ‘grunting’ to describe people? Why would Bishop want to personify the fish?” I prodded. Edita suggested that the speaker begins to see more than a fish, something to eat; she sees a fellow being who has known struggle and deserves respect.

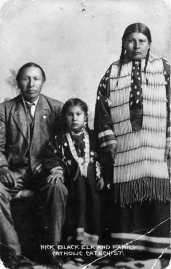

Commending the students’ close-reading interpretations, I asked what figures of speech Bishop uses in these lines to help us to see the fish more clearly. After we noted the skin “like ancient wall-paper” decorated in “rose” patterns and barnacles, “rosettes of lime,” I asked what we begin to notice about this ‘homely’ fish? Edita mentioned the “sea-lice” and “rags of green weed” hanging off its huge body, but she said that the simile and metaphor suggest beauty, not ugliness. Praising her insight, I asked what other images and figures suggest beauty and further personify the fish. We then quickly catalogued the details of Bishop’s portrait: the gills “fresh and crisp with blood,” the “white flesh/packed in like feathers,” the swim-bladder “like a big peony,” the eyes “larger than mine,” the “sullen face” from which “five old pieces of fish-line” hang down “like medals with their ribbons/frayed and wavering,/a five-haired beard of wisdom/trailing for his aching jaw” (ll.25, 27-28, 33-35, 45-63). “So what does the speaker realize as she stares down at the exhausted but honorable old fighter that fills her boat with ‘victory,’ surrounded by a ‘rainbow’ of oily water and rust? (l. 65, 68-75)? Why does she let her ‘victory’ go?” I prodded further. We then discussed the paradox that Bishop develops, the beautiful becoming one with the grotesque. Such wakefulness, we agreed, allowed her—and her readers—to see the respectability, even honor of fellow non-human creatures, insights, I suggested, that Black Elk would have commended.

Randall Jarrell (Source: Poetry Foundation)

As we turned to Bishop’s contemporary, Randall Jarrell, I asked the students what this master teacher and military man insists that we see in “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” beyond the fact stated in the title. With no quick answer coming, I asked Bajram to read the five-line poem aloud:

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

When he finished, I asked for his response to the last line. He said that the speaker uses the past tense, suggesting that he looks back on his own death from the perspective of eternity. “And does he seem at all emotional about the removal of his remains from the plexiglass glass gunner’s station of the bomber?” “No,” he responded, “he describes the removal of his guts as though he were describing the wiping of mud from a windshield.” “Right,” I said, “so matter-of-fact, an everyday occurrence, yet such a shocking image of the consequences of aerial warfare. What do we learn about this victim? How old is he?” I asked. We then wrestled with the equally horrible metaphor in the first line, which describes a baby falling from its “mother’s sleep,” from his mother’s womb, into the “belly,” the womb of the State, the bomber. “How does the verb “fell” underscore the youth of the airman?” I asked. Fidan responded, stressing the almost instantaneous transformation of the infant into a soldier. Complimenting him on his interpretation, I said we would see the same idea explored in Vonnegut’s novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, subtitled The Children’s Crusade, stressing that ‘children’ do most of the dying in wars. “Babies of course come wet from the warm uterus. What happens to the wet baby in the bomber?” I asked. Several voices responded, citing the frozen “wet fur” on the flight jacket. I then asked what they made of the fourth and fifth lines, the reference to getting loose from the “dream of life” and waking to the cacophonous “nightmare” of “black flak.” Arlind suggested that peace must be a dream, an illusion, that reality must be the hell of war. “Why doesn’t Jarrell end of the poem with such a statement,” I wondered. “Who needs it?” Arlind responded. “Precisely,” I said. If we have seen the image, we don’t need a tacked-on moral. It’s all about seeing—and having the courage to keep your eyes open.”

I then invited readings from journals, those prose or poetic accounts of everyday objects or animals that ‘so much depends’ on seeing. Remembering Merita’s reading from her journal the previous week, when she spoke of her frustrations with poetry, her skepticism that ‘so much depends’ on poetry, I feared that no one had responded with a poem. To my delight, hands shot up across the room, and nearly everyone had a poem to share. Many of these poems centered on their memories of their mothers. Blerta, for example, read her poem about her mother’s “sun-beam” smiles; Xhemile described her mother’s “wrinkles” and her “vigorous eyes,” images of her “unconditional love” and her abiding guidance; then Merita brought the whole class to tears with “I See You Coming In,” her memory of her deceased mother:

I see you coming in, little by little, in small steps,

With an albatross round your neck,

I wonder will it ever go away.

You have the snow in your hair; I didn’t notice it’s already winter.

The wrinkles on you face tell that it was heavy all the way through.

I lift you in my arms as you are tall as an eleven-year-old girl,

Oh, no, the great soul of yours makes you big as a mountain.

I kiss your tired face, and then you cry.

Inside your eyes I see a mirror of me.

You kiss me back. Don’t worry, I am fine, you say.

And I want to hold your hand until I count your ages spots

And start over, all over, again, so you don’t ever go for a second time.

As we all mopped our faces and prepared to leave, I thanked those who had read for demonstrating the power and accessibility of poetry. I reminded them, too, that we would sample postmodern fiction next time, as represented by Flannery O’Connor’s story “Good Country People.” After they finished the story, I asked that they write an interpretive response in their journals to the end of the story, where we see another startling revelation, Joy-Hulga in the barn-loft, legless.