February 14, 2012

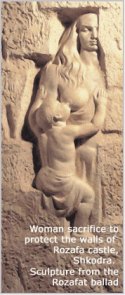

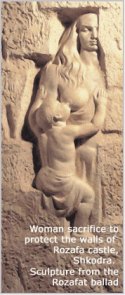

In honor of Valentine’s Day, I’d like to recount a love story honored by Albanians throughout the Balkans, the story of Rozafa. Though the love shared by Rozafa and her husband threads throughout this tale, the central story celebrates Rozafa’s love for her child and for her country.

In brief, the story opens with Rozafa’s husband and two brothers, masons all, building a castle atop the mountain above Shkodra, a fortress where they may defend Albania against its invaders. Mysteriously, however, their fine work crumbles to the ground each night. Just as mysteriously, while the brothers sit idle in despair, three consecutive nights having reduced each day’s work to shambles, a white-bearded old man appears out the mist and explains that their work will never stand until they make a sacrifice. The oxen and sheep already sacrificed won’t do, the old man explains; instead, they must offer the mountain and God a human sacrifice, one of their own wives. Before he vanishes, the old man swears the three brothers to secrecy, explaining that the wife who must die will be the one who brings them their lunches the next day.

Predictably, fearing the loss of their wives, the two oldest brothers break their pledges, whispering in the night to their wives that they must not come to the work site the next day. The younger brother, Rozafa’s husband, has the same fear, but he keeps his pledge, his “besa,” the center of Albanian ethics and morality.

The next morning, when the brothers’ mother has prepared the lunches, the wives of the eldest sons make excuses when the mother-in-law asks for their help with delivery. Rozafa, ignorant of the call for a human sacrifice, cheerfully agrees to take the food to her brothers-in-law and her husband.

When the youngest brother sees his Rozafa coming with their bread and fruit, their water and wine, he “dropped his hammer upon the stone, splitting it in two, as if his heart had just broken.” With his youngest brother ghostly pale and speechless, the oldest brother, his head held in shame, explains to Rozafa that the castle walls “will not stay up without a living sacrifice,” that this person, chosen by “chance,” must be immured in the castle. Recovering quickly from this shocking revelation, Rozafa comforts her husband with her “trembling hand” and pronounces herself “ready” to become one with the wall. She also urges her husband and his brothers to play their roles in protecting Albania, to carry themselves “high, as high as the castle walls, for the people are waiting for you all to finish your work.”

(Source: Albanaian Canadian League Information Service--click image to view)

Before they begin their grim task, however, Rozafa pleads that they immure her in such a way so that “my right eye, my right foot, my right hand, and my right breast are left out through the stone.” In this position, she explains, she can watch her baby, “cradle him with my foot, caress him with my hand, and nurse him with my breast.” Such nurture will pay off, she prophecies: just as the castle will protect against invaders, so her son “may be king one day and reign upon this proud land.”

Though the narrator of the tale provides no details on the fate of Rozafa’s son, he does assure us that her wishes were “honoured” and that “even today, after many hundreds of generations, her castle remains high above the city of Shkodra in northern Albania.” Having lived there for six months, I can vouch for the narrator’s veracity. I can vouch, too, for his claim that “the white stones of the castle…are continuously damp,” damp, as legend has it, with “the tears of Rozafa and the milk of her breast” (see photos of the Citadel of Rozafa).

**Click on the first picture to scroll through the gallery in a larger format.

-

-

Citadel of Rozafa, damp with her tears and milk

-

-

View from Citadel of Rozafa

Credits: The quotes from my summary of Rozafa’s love story come from Mustafa Tukaj’s “Rozafa’s Castle,” published in Faith and Fairies, a collection of stories edited by Joanne M. Ayers and published by Skodrinon Press, 2002. Also, the last three paragraphs come, almost verbatim, from my article “Albania Immured: Rozafa, Kadare, and the Sacrifice of Truth,” published in the South Atlantic Review, Vol. 71, No. 4, Fall 2006. Finally, since I would not be in Kosova without the support of my Valentines, I would like to picture them here, my mom Kay, and my wife Judy.

My Valentines: my mom Kay (L), and my wife Judy (R)

After a journey that took her from Mississippi to Houston to Canada to Austria and finally to Kosovo, Judy arrived in Prishtinë on May 13. She’s a site for these sore eyes!

After a journey that took her from Mississippi to Houston to Canada to Austria and finally to Kosovo, Judy arrived in Prishtinë on May 13. She’s a site for these sore eyes!