February 5, 2012

Today I rediscovered the difference between religion and spirituality. Overlaps abound, of course, both rooted in a longing for connection to something larger than self, to an energy that intersects our illusion of time but lives beyond time. But if one may draw inferences from the pages of history books, religion has too often been about buildings, codes of conduct, sacred spots—and therefore about disputes, exclusions, and executions. Spirituality, in contrast, has always been about visions of unity, with that “energy,” yes, but also with Others, with critters, and with the earth, the garden that sustains us and honors our work.

I experienced such spirituality this morning, when I attended a service at the Bashkësia e Popullit të Zotit (Fellowship of the Lord’s People)** in Pristina. Centered on the Protestant Christian faith, the Fellowship offered plenty of religion in the best sense of the word, as reflected primarily in the sermon on Revelations 2 and the charge to show love for Jesus by doing his work. But I found myself moved primarily by the spirituality in the room, a communal unity engendered by guitars, keyboards, and singing, by story-centered pleas—offered in Albanian and in English—to support on-going efforts to relieve poverty and suffering, and by the blend of humanity—Albanians, Germans, Canadians, Americans, women and men, kids and parents, babies and elders, black and white—eating bread together in peace.

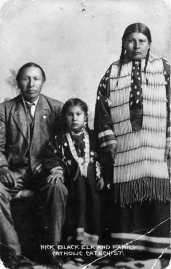

After the service, I found more such spirituality in John Neihardt’s Black Elk Speaks and in N. Scott Momaday’s The Way to Rainy Mountain, works I will read with my Pristina students. Having interviewed Black Elk in 1930, Nebraska poet John Neihardt then wrote his book celebrating the vision of world unity this Lakota holy man experienced as a boy, a vision that empowered Black Elk to preserve his people from the relentless westward movement of the Wasishus on their “iron road” and on the mounts of the US Cavalry. By securing his “nation’s circle,” Black Elk would also unite animals and people “like relatives”; he would then ensure that the “hoop” of his people blend with the hoops of all peoples, forming “one circle” around the “holy” tree of life.

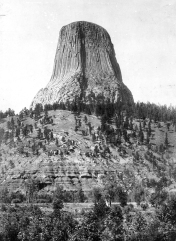

Bringing his love and respect for his grandmother to her grave on Rainy Mountain, N. Scott Momaday offers an equally passionate vision of unity, focusing not on what might have been but on what was, the “courage and pride” of the Kiowa people, great “horsemen,” warriors, and artists who derived their power from the Tai-me, the sacred Sun Dance doll. Kiowas expressed this spirituality not only in dance and in “reverence for the sun” but also in their love “for the eagle and the elk, the badger and the bear,’ for the “billowing clouds” whose shadows “move upon the grain like water,” for the Big Horn River, for the Devil’s Tower, where “in the birth of time the core of the earth had broken through.” And they prayed. Momaday recalls the last time he saw his grandmother: “She prayed standing beside her bed at night, naked to the waist….Her long black hair…lay upon her shoulders and across her breasts like a shawl.”

Devil's Tower, c. 1900, US Geological Survey, Photographer: N. Dalton (Source: Wikipedia--click image to view)

Of course, Black Elk’s vision of unity never came true, and the Kiowas one day “surrendered to soldiers at Fort Sill.” Deprived of their Sun Dance, many spent the rest of their days with “the affliction of defeat,” tormented by a far darker vision of “deicide,” their nation crushed by another with “Manifest Destiny,” religion at its worst.

__________________________________________

**Links related to the Fellowship of the Lord’s People:

- Children’s Camp Report–July 2011

- Article about Kosovo Protestants–Dec 2010, highlighting interview with Pastor Artur Krasniqi

- Kosova Protestant Evangelical Church, denomination to which the Fellowship of the Lord’s People belongs

![Faculty of Filologjik_1 feb 2012 Fakulteti i Filologjisë (Faculty [College] of Philology)](https://reflectionsonkosovo.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/faculty-of-filologjik_1-feb-2012.jpg?w=300&h=225)