June 2, 2012

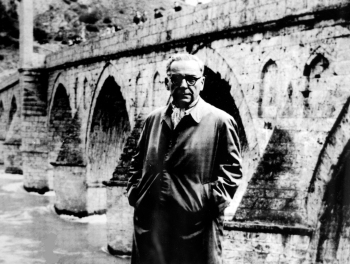

In 1998, Mr. Vonnegut returned to Dresden, Germany; he revisited the slaughterhouse that served as an air-raid shelter during World War II where he and his fellow prisoners of war survived the fire bombing of Dresden. (Source: New York Times; Photo credit: Matthias Rietschel/Associated Press)

As the students settled in for our next session, Ragip accepted my invitation to read aloud the first two pages of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. When he finished, we talked about the autobiographical nature of this preface to fiction, Vonnegut’s insistence that “all this happened, more or less,” that shortly after Dresden had been fire-bombed to ashes, a soldier much like the character Edgar Derby really did get shot by a firing squad “for taking a teapot” from among the ruins, that a soldier much like Paul Lazzaro really did pledge to murder one day those who slighted him or his friends during the war, that Vonnegut “really did go back” to Dresden in 1967 with his “old war buddy” Bernard V. O’Hare to visit the Dresden slaughterhouse where they had spent their nights as prisoners of war (p. 1). After I asked why Vonnegut would want to stress this factual basis for his fiction, our conversation, much to my delight, turned back to Ernest Gaines, whose fiction about injustice and transformation also rooted in Gaines’s experience growing up in Louisiana in the 1930s and ‘40s, and to William Faulkner, who challenged all fiction writers to tell the truth about human brutality and the conflicts of the human heart, but also to uplift readers with evidence of “compassion” and “sacrifice.” Having congratulated the students on their insights to the great paradox of literature, the fictions that reveal truths, I asked them to keep Faulkner’s speech in mind as we discussed Vonnegut’s novel. “Has Vonnegut written one of those visions of despair that Faulkner condemned, or does he manage to tell these terrifying truths and, at the same time, to inspire hope that we—as individuals and as a culture—might not only endure but ‘prevail.’”

First edition cover of Slaughterhouse-Five: Or the Children’s Crusade (Source: Wikipedia)

Leaving this question hanging in the air, I noted Vonnegut’s admission of the futility of writing an “anti-war book” (p. 4), which he follows immediately with a description of himself in the late-1960s, materially comfortable but given to drinking too much and making late-night phone calls to old veterans of World War II (p. 5). “Does this description clarify why he would write this book, if he considers its anti-war position pointless?” I asked. Albana said that he seems haunted by the past, which leads to self-destructive behaviors but also to the need to talk to those who remember. “Maybe the writing comes from this same need to talk about it,” she offered. “Yes,” I responded, “and notice that he feels compelled to tell us again, the second time in six pages, that the story will end with ‘the execution of Edgar Derby’ (p. 6). Can you name another work we have read where we find out about the ending, an execution, on the first page?” Many voices responded with Gaines’s Lesson and the promised execution of another good man, Jefferson. “How might this up-front emphasis on the brutal, senseless death of a good man relate to the Faulknerian challenge for uplifting fiction?” I asked. Besa responded, suggesting the symbolic power of both executions, images simultaneously revealing our capacities for mindless cruelty and for goodness.

Applauding Besa’s interpretation, I asked the class to consider another image that Vonnegut juxtaposes to the execution of Derby, that of the “rabid little American” Lazzaro heading home from the war with “emeralds and rubies” he snatched from dead people “in the cellars of Dresden” (pp. 7-8). “Did you notice that after both images, Derby’s death and Lazzaro’s violation of the dead, the narrator says, ‘So it goes’? What do you make of this refrain, which you’ll hear throughout the novel?” Fidan suggested that line acknowledges not just the inevitability of death but also our inability to explain the injustice of men like Derby dying and men like Lazzaro thriving. “It just happens,” he said.

Naturally, I commended this intelligent remark but also stressed Vonnegut’s postmodern need to tell the story, to help us see what happened, however futile his protest against war and against “plain old death” might seem (p. 4). Vonnegut admits, I continued, that his story has generated a “short and jumbled and jangled” book because “there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre” (p. 24); still, he must write to set the record straight, to discredit versions of reality that ignore or hide that record. “Can you recall examples from chapter one of Vonnegut exposing others’ invitations to close our eyes to the truth?” I asked. Blerta mentioned Vonnegut’s anthropology professor, who teaches that “nobody was ridiculous or bad or disgusting,” a theory that would make no distinction between Derby and Lazzaro (p. 10). Her example sparked Gezim’s comments on Vonnegut’s boss, a man whose military service took him no further than Baltimore, who sneers at Vonnegut as an enlisted man and approves of war as a way for officers to advance. Gezim then quoted Vonnegut’s reflection on this smug non-combatant: “the ones who hated war the most were the ones who’d really fought” (p. 13).

“What about the episode at the O’Hare house? What terrible truth about war does Vonnegut insist that we see here?” I prodded. Hearing no answer, I asked, “Why do you think that Vonnegut mentions taking his daughter and her friend with him when he visits O’Hare to talk about the war?” Dafina said they he took the girls along just to see Cape Cod (p. 15). “Yes, I agreed, “but he has Dresden on his mind, and he knows that among the masses who died in the firestorm were thousands of little girls. How does one explain fire-bombing to children? Do you recall why Mary O’Hare, to whom Vonnegut dedicates his novel, initially resents Vonnegut’s visit? What does she assume his book will declare about war?” Albana promptly cited Mary’s anger, believing that Vonnegut would write a novel celebrating war, hiding the fact that “babies,” not men, do most of the dying (p. 18). “Yes,” I said, “and do you remember Jarrell’s “Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” the ‘baby’ who dies in the belly of the bomber? How does Vonnegut respond to Mary?” Albana answered again, quoting Vonnegut’s promise to tell the truth about the “Children’s Crusade” in World War II, much like the Children’s Crusade that Vonnegut and O’Hare read about from the thirteenth century, when thousands of children were forced to fight in Palestine and then sold into sexual slavery (p. 20). Thanking Albana, I asked the class if they could explain why Vonnegut ends this chapter with an allusion to the Biblical story about Lot’s wife. Finding the reference, we all quickly agreed that Vonnegut the writer, like Lot’s wife, must “look back,” and he insists that we look, too.