April 21, 2012

Li-Young Lee (Source: timesunion.com)

Turning our attention to Li-Young Lee’s poem “The Gift,” I began with the obvious but important fact that Lee’s poem establishes as we come to it from the work of Plath and Dove, namely, that men share with women this intense need to remember their fathers clearly, to ‘get back’ at them or to them, to understand them and love them, perhaps to forgive them, perhaps to get past them. “Do you recall from the introduction what distinctions Lee’s father achieved?” I wondered. Several voices responded with “physician to Chairman Mao” and “political prisoner in Sukarno’s Indonesian jail.” “Right,” I said, “and our editors also credit Lee with using the same techniques that Dove used in resurrecting her remorseful but menacing father, relying on multi-sensory appeals to recreate his father and to remember him faithfully and accurately.”

Noting that the word “gift” never appears in the poem, except in the title, I asked, “What is it?” Arlind responded with “his ‘stories,’” Dafina with “his ‘tenderness’ and ‘discipline.’” Praising both answers, I asked how Lee uses sensory imagery to reveal that tenderness and firmness. We then explored Lee’s use of synecdoche and metaphor, the “voice” that sounds like “a well of dark water,” the “hands” that embrace Lee’s young face but also raise “flames of discipline” over his head (ll. 1-13). We then noticed the long-term effect of these remembered images, as Lee sees himself, years later, lifting a splinter from his wife’s hand with the same healing gentleness that his father had ‘planted’ in his hand decades before. “And how does Lee express his gratitude for these gifts?” I asked. Edita responded by citing “what a child does….I kissed my father” (ll. 33, 35).

“When you juxtapose Lee’s poem to Plath’s “Daddy,” or even to Miller’s play Death of a Salesman, what do you realize about the American family and about the need of grown children to look back and understand their parents?” I asked. This prompt led to some interesting comments on the need of children to reconstruct family narratives of justice and love as well as stories of injustice and abuse. “What do adult children receive, other than some joy and lots of pain, from remembering such stories?” I wondered. “Is it just about assigning blame, condemning mom or dad for what we have become? Or about kissing the parent who loved you well?” Wisely, Merita responded, “It’s more about the adult child making a choice, saying ‘you had the wrong dream,’ or ‘I’m through,’ or ‘I choose to pass on your love to my family.’”

Louise Glück (Source: Washington University in St. Louis News)

Applauding this perceptive insight, I asked the class where Louise Glück’s poem “Appearances” stands on spectrum of remembering family narratives and choosing what the next chapter will be. After Laureta read the poem aloud, I reminded the class of the introductory comments on Glück’s “complex family relations,” her psychoanalysis to deal with the resulting pain (3000), and then asked where they saw pain and coping mechanisms in the poem. We quickly caught the reference to being “analyzed” but also the humor, the reference to portraits of her and her sister hung “over the mantel,/ where we couldn’t fight” (ll. 2-3). When I asked what she remembers about her mother, we reviewed key descriptors of the “strong,” ‘controlling’ woman who valued “order,” who grieved always over another daughter who died, who “ministered to” her living sister and, in so doing, “damaged the other” (ll. 28-36). “So what does the adult child now realize about the consequences of her mother’s unequal love?” I asked. Besa rose to the challenge: “She understands that because she always wanted to be “child enough” for her mother, she became “too obedient,” too ready to be shaped—“If you want me to be a nun, I’ll be a nun”—to earn her mother’s approval (ll. 26, 43-44).

Yusef Komunyakaa (Source: Indiana Review)

“Yes,” I responded, “and such realizations can liberate the adult, as we saw in Biff at the end of Salesman. Isn’t it interesting that when adult children take a different route than the parents took, they usually do not try to ‘kill’ the parent, as did Plath; on the contrary, they try to preserve the parent, as did Biff.” I then asked if they could recall where Yusef Komunyakaa got his name and how that naming might relate to the instinct to preserve the parent. No one remembered, so we scanned the introduction for this sentence: Komunyakaa “adopted the lost surname of a Trinidadian grandfather who came to the United States as a child” (3075).

Noting, too, the statement that Komunyakaa devoted his poetry to restoring black faces—from rural Louisiana, from Bourbon Street, and from Vietnam—that have been ‘erased’ from cultural memory (3075), we sought to discover how he remembers his father in “My Father’s Love Letters.” After Fidan read the poem aloud, we spoke of this illiterate alcoholic mill worker, who asked his son to write his love letters to his wife, “promising to never beat her/Again” (ll. 6-7). “But what else does Komunyakaa refuse to erase?” I asked. Arben answered, listing the tools of his trade, the “carpenter’s apron,” the “gleam of a five-pound wedge” that “pulled a sunset/Through the doorway of his toolshed” (ll. 12, 22, 24-25). “Right,” I said, “and he also remembers that his father could look at a blueprint and instantly know ‘how many bricks/Formed each wall’” (ll. 30-31). Asked for his conclusion, Arben added that the drunken brute also seems to be a true craftsman, an artist “almost redeemed by what he tried to say” in his letters (ll. 35-36).

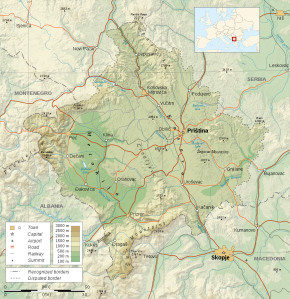

Thanking all for their patient, insightful readings, I asked for volunteers to read from their journals about their parents. Bajram responded with a full-page tribute to his mother, the “goddess” who never failed him as he grew from childhood to adolescence and manhood. Though he had not attempted poetry, we all praised the poetic quality of his prose, poetic in the sense that it relied on imagery from her kitchen table, site for buttering home-made bread and learning letters, and from his bedside to stress her nurturing tenderness, and from the war—school doors closed, soldiers ruling the streets—to stress her dignity and courage in a time when ethnic cleansings made it difficult to sustain either quality. Thoroughly impressed by Bajram’s tribute, I thanked him for celebrating the ‘gifts’ his mother provided, much as Li-Young Lee had done in his poem about his father.