February 29, 2012

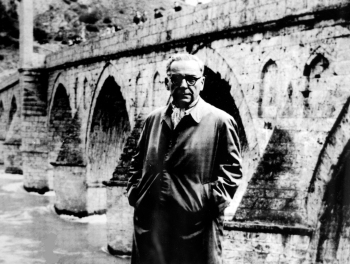

Yugoslavian diplomat Ivo Andrić died in 1975, but Bosnia and the Balkans honor him, as does the world, not only for his diplomacy but also for his fiction, particularly The Bridge on the Drina, which won him the Nobel Prize in 1961.

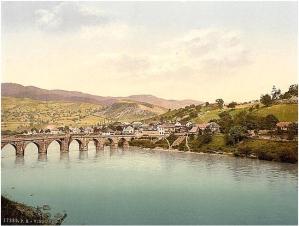

Set in Andrić’s native Bosnia, this historical novel spans three hundred years, beginning with the new wave of Ottomans in the late sixteenth century and ending with 1914 and the start of World War I, the life-time of the magnificent bridge that spanned the Drina River. Covering this period with the precision of a scholar, Andrić narrates the parade of Turkish and Austrian powers that occupied this stunning mountainous region, but with the eye and heart of a poet Andrić populates this vast canvas with images of human beings so ordinary in their capacities for celebration and passion, so extraordinary in their capacities for brutality and courage.

The novel begins with indelible images of the brutality that grows from the lust for power and land. Though eventually a work of engineering art, its “eleven arches…perfect and wondrous in its beauty” (64), the bridge begins when a Turkish Vezir arrives and conscripts laborers, beating and even killing any man who resists, turning this town on the Drina “into a hell, a devil’s dance of incomprehensible works, of smoke, dust, shouts, and tumult” (29, 31). Painfully aware that the bridge will benefit Turks, not Bosnians, workers grumble; some even plot to sabotage the bridge. Enraged by such covert resistance, the Vezir finds a scapegoat, a brave peasant who pays for his alleged sabotage by having his toenails torn from his feet, his chest wrapped in red-hot chains, and his anus pierced by a pike that runs out through the back of his neck. Raised high on the emerging bridge for all would-be resisters to see, the impaled peasant “writhed convulsively” for hours before dying, just as the Vezir ordered (49).

We see the same brutality at the end of the novel, when World War I releases the “wild beast” inside us all that “does not dare to show itself until the barriers of law and custom have been removed” (282). That beast obliterates this town and even its seemingly indestructible bridge, as a bomb planted on a pier causes it to “crumble away like a necklace; and once it began no one could hold it back” (313). Perhaps the greatest cruelty, the survivors have no home, no place.

But between these bookends revealing our hearts of darkness, Andrić paints lighter hearts of those over these three centuries who take joy in simple pleasures, like fishing under the bridge (15) or meeting on the bridge to exchange flirtatious glances, to celebrate weddings, or to drink brandy and tell stories (19-21).

When William Faulkner accepted his Nobel Prize in Stockholm in 1950, he called on novelists not to paint portraits of despair; instead, he challenged writers to celebrate our strength, our ability not only to “endure” but to “prevail.” As though accepting Faulkner’s charge, Andrić describes hearts capable not only of simple joys but also of endurance, as these Bosnians must suffer floods and droughts as well as invasions (76-79). Following another Faulknerian challenge, to tell stories of the human heart “in conflict with itself,” Andrić weaves together numerous tales of such inner-conflict we can expect to find in any century, such as Peter’s struggle with his addictive gambling (145-152); Fata’s torment over a marriage, having to obey her father or to obey her heart (104-112); or Zorka’s agony over two men, having to choose a good man who loves her but for whom she feels no love, or to wait for a lesser man indifferent to her passion (276-281).

Finally, Faulkner urged writers to uplift us with stories of human beings—however few—who show “compassion” for others and the willingness to “sacrifice” to relieve others’ pain. Among several of Andrić’s characters who fit this description, Lotte stands tallest. We meet her first in the middle of the novel, a beautiful young widow with “ivory white skin, black hair, smoldering eyes,” and a “free tongue,” and therefore enough brass to start a hotel in a patriarchal culture (177). Far more than a shrewd business woman, Lotte serves as benefactress to many families, providing counseling and money for those whose lives have run amuck (180). By the end of the novel, Lotte has “grown old. Of her onetime beauty only traces remained” (257). Unconcerned about her physical decline, Lotte worries instead about her ability to help others. As the town has declined, Lotte’s once prosperous hotel has declined, too. As a result, she suffers nightly over those in “hopeless poverty” that she can no longer relieve. Though “tired” to the soul, Lotte still gives others what she has left, her sage counsel (262). When we last see her, just before the bridge falls into the Drina, Lotte crosses bridge with a few other displaced old women—and with a “sickly child on a push-cart” (300).

Thanks to this Nobel Prize winner, then, no history of the Balkans can be complete that finds only cruelty in the human heart.

Andric, The Bridge on the Drina, a story that portrays a mountaneous region unified by a bridge that represents Ottoman rule eager for land and power. Its a vivid history of the tribulations and courage of the local people. Literally its about a bridge over Drina river given as a gift from Vezir. We also see simple and common lives of people who take joy in pleasures such as fishing and drinking in the period to follow the construction of the bridge. The story is uplifing because we see real to life characters such as Zorka, and Fata preoccupied with their inner struggles between passion and customs. Andric depicted the ways people struggled to shape their lives during the ottoman rule.

I have enjoyed reading this review of I.Andric’s “The Bridge on the River Drina”. I especially liked when you say that “with the eye and heart of a poet Andrić populates this vast canvas with images of human beings so ordinary in their capacities for celebration and passion, so extraordinary in their capacities for brutality and courage”. Furthermore, drawing a parallel in between Faulkner’s Nobel Prize speech and his call for the novelists to “celebrate our strength, our ability not only to endure but to prevail” and Andric’s novel is quite interesting: “accepting Faulkner’s charge, Andrić describes hearts capable not only of simple joys but also of endurance, as these Bosnians must suffer floods and droughts as well as invasions (76-79). Following another Faulknerian challenge, to tell stories of the human heart “in conflict with itself,” Andrić weaves together numerous tales of such inner-conflict we can expect to find in any century”. Definitely next on my to- read list 🙂

Another well written response. Thanks, Merita.

RR

The bridge on the Drina – Ivo Andric

This short review makes to admire the writer’s novel.

It’s pity when considering that historical time, when some people in their mother land, such Bosnians, are forced to do something unwillingly and tortured consequently. I find a little bit surprising how such a bridge, built upon misery and cruelty, later turns out to be a kind of symbol when local people spend their particular moments of their joy and happiness. Yet, I really like the fact that something, made by such cruelty and misery, has been shifted into something positive and inspiring for people’s life and be forgotten something that was bad.

I enjoyed your perceptive comment, Lirdona.

I like the way how the poets write and I enjoy reading their novels not because that they write something that I agree or not, as I like the essay written by the professor Raymond. But I disagree with some responders who describe the bridge: “one that represents Ottoman rule eager for land and power”. When it comes to Turkish Empire we have to go back to history books to learn the truth because that is not true that they were eager for land. They had another mission. However, this is another wonderfully written essay by the professor about the Nobel Prize Winner, Ivo Andric’s novel The Bridge on the Drina and it is worth reading, of course.

Thanks, Fidan. I know that the Ottomans had a range of interests, but ‘the Ottoman Empire had no interest in acquiring land’!? Hmmm…I’ll have to think about that!